There are various hypotheses about the role of behavior and speciation. One of these is the evolution of mate choice, where a genetic variant results in a phenotype that potential mates respond to, and the response is also under genetic control. This requires the simultaneous evolution of at least two loci (the signal and the behavioral response) and a problem with this line of reasoning is that the alleles at the two genes can quickly recombine away from each other unless they are genetically close together along a chromosome (and/or recombination is suppressed by a chromosomal rearrangement). Another theory is the "good genes" hypothesis. That an individual with advantageous alleles can also signal this phenotypically and mates will choose these individuals (a cool example of this is meiotic drive suppression in stalk eyed flies).

This is interesting. Two studies just came out, one in the zebra finch (http://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822%2816%2930400-6) and another study in the canary (http://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822%2816%2930401-8), and found that the gene responsible for variation in red pigment in the beak and feathers is due to expression levels of CYP2J19. Interestingly, this pigment is also used in the retinas to screen certain colors of light. And, it is expressed in the liver. Many of the CYP family (a.k.a. the Cytochrome P450 family) of genes are involved in detoxification of a range of compounds.

This is purely speculative, I have not had time to investigate what is known about CYP2J19's precise functions, but what if CYP2J19 in birds acted simultaneously as a mate choice signal (beaks and feather pigment) and a component in the behavioral response (retina pigment/light sensitivity filter) and maybe also had a "good genes" role as well (liver detoxification)? (See also the "green-beard effect" which CYP2J19 variation may also be a candidate for.)

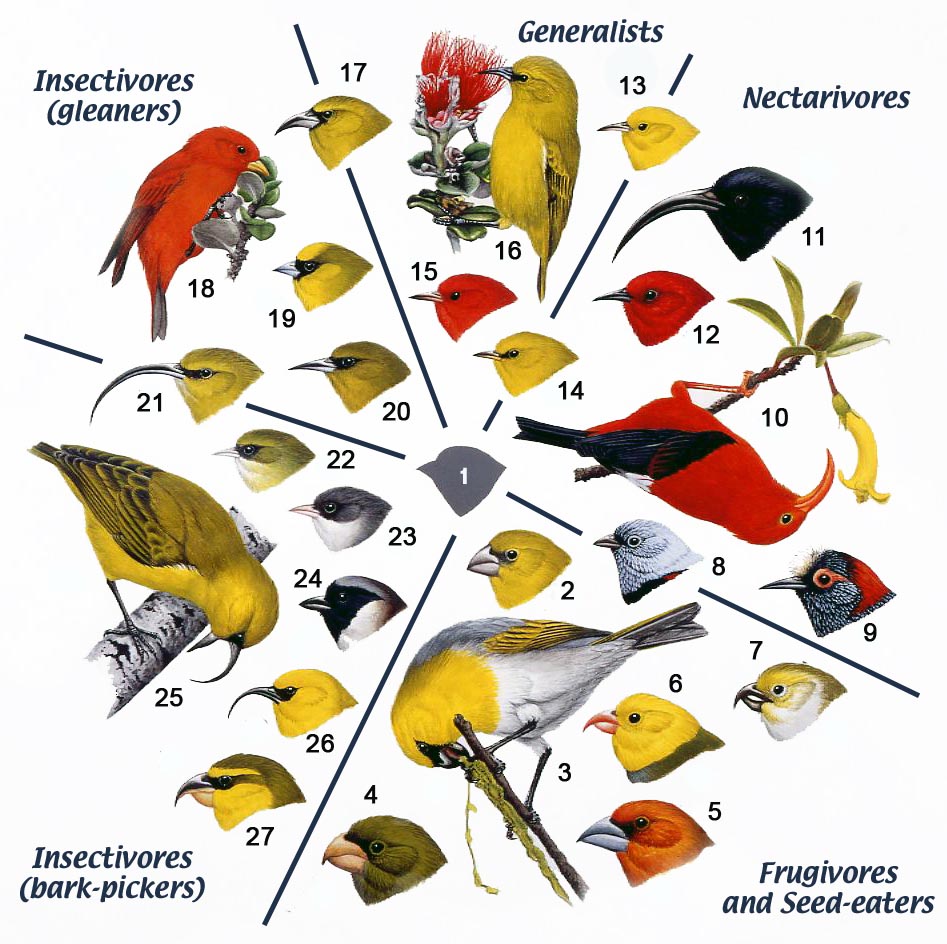

Regardless, this should be followed up in other groups of birds. There are rapid speciation events associated with transitions between red and yellow plumage and a comparative study of DNA variation at CYP2J19 in groups like the Hawaiian honeycreepers might be enlightening.